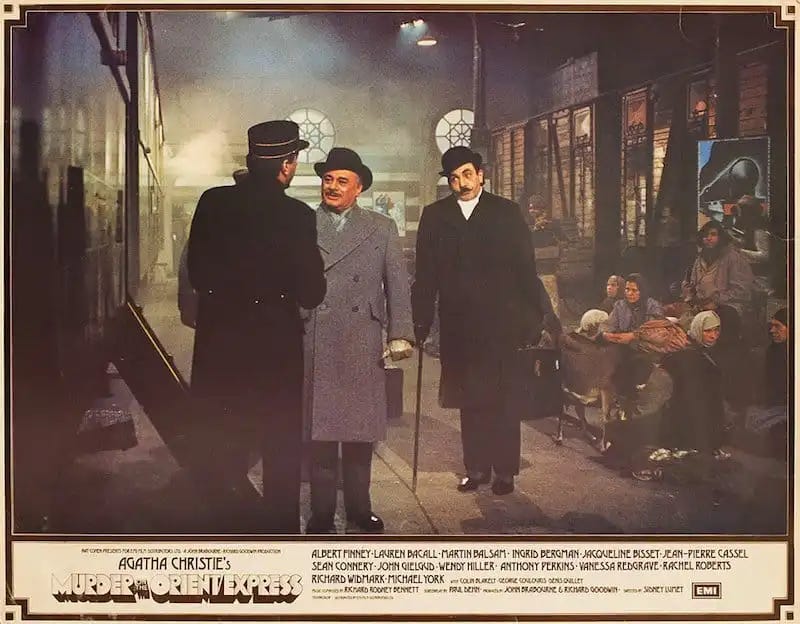

Murder on the Orient Express (1974)

"I have often felt, sir, that instead of our employers requiring references from us, we should require references from them..."

Welcome back to WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups. This Sunday, in our regular post for free subscribers, it’s all aboard the Orient Express for a cracking tale of mystery, intrigue, and murder — a first-class ticket to another era, with more than a hint of Disco Deco, haunted by the shadow of a real-life tragedy.

“It was a great train in 1929, and it goes without saying that the Orient Express is the most famous train in the world, like the Trans-Siberian, it links Europe with Asia, which accounts for some of its romance But it has also been hallowed by fiction: restless Lady Chatterley took it, so did Hercule Poirot and James Bond, Graham Greene sent some of his prowling unbelievers on it, even before he took it himself…”

Paul Theroux, The Great Railway Bazaar (1975).

And to Hercule Poirot, Graham Greene, and Mister Bond, we must add Dr. Van Helsing, on the hunt for Dracula; Harry Flashman and Phileas Fogg; and in real life, Alan Whicker, Arthur Daley, and Cheryl Ladd — in search of love in a made-for-television romance from 1985. It is at this stage, alas, that I must confess to a non-acquaintance with the Orient Express as a passenger — or at least, with the real McCoy, which ran its final service in 2009. As with Concorde, I have missed the boat. And I’m not entirely convinced by the modern re-creation, which smacks of a cruise, (oh, to join the Captain’s Table!), or one of those hearty Murder Mystery Weekends held at a Mock Tudor hotel in Surrey. I don’t possess a white dinner jacket, and I’m a miserable failure on the rubber chicken circuit, smarming up to the worthies (retired accountants and their lady wives). Far too chummy for my liking.

The Orient Express, which embarked on its first journey in the summer of 1883, was the world’s first true luxury train — the brainchild of Belgian banker’s son George Nagelmackers, a most admirable man and the founder of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits. I have a thing about restaurant dining cars. Until 2009, on the Flying Scotsman, the admirable GNER served kippers on porcelain emblazoned with the company crest. And for the record, the first menu ever served aboard the Orient Express — at a special inaugural dinner in October 1882, before regular service began — featured oysters, soup with Italian pasta, turbot with green sauce, chicken ‘à la chasseur’, fillet of beef with ‘château’ potatoes, ‘chaud-froid’ of game, lettuce, chocolate pudding, and a buffet of desserts.

What I hadn’t fully grasped, until researching this post, was that in 1934 — the year Agatha Christie’s novel was first published — the Orient Express ran on more than one route. The original line travelled from Paris to Bucharest (and then by boat to Istanbul), passing through France, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania. Meanwhile, the Simplon Orient Express — the route featured in Christie’s novel — had opened in 1919, running from Paris to Istanbul via the newly constructed Simplon Tunnel on the Swiss–Italian border, then on through Milan, Venice, Belgrade, and Sofia before finally reaching its destination.

Which brings us to Sidney Lumet’s Murder on the Orient Express — the 1974 version (I can barely bring myself to mention the 2017 remake) — which, I think, set the benchmark for the glamorous, star-studded big-screen Agatha Christies to follow: Death on the Nile (1978), The Mirror Crack’d (1980), Evil Under the Sun (1982), and Michael Winner’s Appointment with Death (1988). Christie aficionados, please correct me if I’m wrong — I have a feeling that Murder on the Orient Express (1974) may have been the first Agatha Christie adaptation since George Pollock’s Murder Most Foul (1964), which starred Margaret Rutherford as a decidedly black-and-white Miss Marple. A very different kettle of kippers. Although thinking about it now, I’ve managed to forget Endless Night (1972), starring Hayley Mills, Hywel Bennett, and Britt Ekland — a psychological thriller with Gothic overtones.

Interesting choice of director, Sidney Lumet. And we must add to our list a clutch of Lumet films: Fail Safe (1964), The Deadly Affair (1967) and Deathtrap (1982), based on the Ira Levin play (a homage to Sleuth [1973]), which we covered last year. For those of us who appreciate the glittering allure of Disco Deco, 1974 was a seminal year for the 1920s and 30s revival — and actually, when you think about it, only a mere forty years from the publication of Murder on the Orient Express in 1934. Suddenly, the 20s and 30s were back in fashion — for as we have explored in previous posts, this glittering, and sometimes, depressed era provided rich pickings for filmmakers, admen, antiques dealers, designers, fashionistas and tastemakers, and those of an influential bent: a now forgotten style which began in the late 1960s and lingered until the late 1970s, or even the very early 1980s. From Bonnie & Clyde (1967) to Bugsy Malone (1976), from The Great Gatsby (1974) to The Sting (1973), from Cabaret (1972) to Chinatown (1974), the suede glamour of Disco Deco ruled supreme — a look championed by Barbara Hulanicki’s ‘Big’ Biba flagship emporium, which, in 1973, opened in Kensington High Street and where among the whisperings, the Liebfraumilch and the palms, one might buy a knitted cloche hat, an Egyptian bauble or a black and gold tin of Oxtail Soup decorated with Deco graphics. Upstairs, on the fifth floor of the old Derry & Toms building, the Rainbow Room served an eclectic menu, English nursery food meets San Francisco hippie: Fish Tart, Briani with Yoghourt (sic), Pouffs Pudding (yes, really!) and Hindi Dessert, washed down with sparkling Cold Duck (£2.50) — a Teutonic sparkling wine made in the United States.

And of the 1970s and 80s big-screen Christies, Murder on the Orient Express (1974), I think, is the original and the best. And the most elegant. As much as I enjoy the atmospheric Death on the Nile (1978) with She-Who-Can-Do-No-Wrong Lois Chiles, and its exotic locations — and the voguish, Eighties romp which is Evil Under the Sun (1982), more Anthony Shaffer than Agatha Christie. Murder on the Orient Express (1974) is beautifully considered: from the uber-stylish Deco titles, a pastiche of A. M. Cassandre’s poster graphics to Sir Richard Rodney Bennett’s fabulous soundtrack — a distinguished classical composer and jazz pianist in his own right. And another thing: There’s no CGI. The kidult curse of today’s cinema. This is a real steam locomotive. These are real carriages (from the original Orient Express) and this is real countryside, even if it’s France standing in for 1930s Yugoslavia. And, apparently, real snow.

Surprisingly, the last steam engine to run on the French mainline was in 1975, so SNCF, even then, had working steam locomotives and trained engine drivers who knew how to run them. So there’s that lovely atmospheric shot of the departing train, taken in one go, as Sidney Lumet had limited time to complete. I like how the camera lingers as the red warning light of the last coach glides off into the smoke, steam and mist, even if the railway nerds grumble that, historically, the locomotive pulling the train would have been replaced at every national border. I suppose to modern eyes, Murder on the Orient Express now seems rather 70s, when actually, with its soft, diffused natural light, it’s more like the 1930s as seen from the point of view of the 1970s. There’s a sense of claustrophobia. Of being on a real train.

And rereading Murder on the Orient Express, I’m struck by Agatha Christie’s spare, economical prose. Just how good Agatha Christie is as a writer. Here she is describing Miss Debenham (in the film played by Vanessa Redgrave):

When Mary Debenham entered the dining-car she confirmed Poirot’s previous estimate of her. She was very neatly dressed in a little black suit with a French grey shirt, and the smooth waves of her dark hair were neat and unruffled. Her manner was as calm and unruffled as her hair.

My late mother-in-law once attended a dinner party hosted by her friend, the distinguished novelist and historical biographer Elizabeth Jenkins, at her Regency house in Downshire Hill, Hampstead, where Agatha Christie — and her husband, the archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan, were fellow guests — a party held, I suspect, in honour of the Balham Priory poisoning, one of the most scandalous cause célebrès of the Victorian era (Venetia is descended from the infamous Dr. Gully, Agatha Christie’s prime suspect in this most fascinating of cases — it’s a long story.) My mother-in-law spent the evening charming Sir Max “a delightful man”, summarily dismissing Dame Agatha as “curiously disappointing, didn’t say a word”, when, in fact, I suspect Dame Agatha was quietly observing and analysing her every move, and every word, from the other side of the shiny mahogany dining table.

There's a sense of a haunted past in Agatha Christie, deadly secrets resurfacing to haunt the present, a hiker discovers a body on a Surrey Heath, helmeted and caped policeman drag the moors, the mysterious disappearance (and demise) of the famous aviator, Captain (Michael) Seton, haunts Peril at End House (1932), my favourite Christie novel, so far. In Murder on the Orient Express, Christie based Colonel (John) Armstrong VC (an American who had served in the British Army) on the aviator Charles Lindbergh, the first to fly, alone, from New York to Paris non-stop. An international sensation at the time. In 1932, Lindbergh's two-year-old son, Charles, was kidnapped, held to ransom, and found dead, partially decomposed and devoured by animals (it's just too appalling) in a lonely woodland a few miles from the Lindbergh estate in New Jersey — a dreadful tragedy, which, again, fuelled further sensation in the world's press, leading to a sequence of tragic repercussions, like a pack of poisoned playing cards. This included the suicide of Charles Jr.'s English nursemaid, poor Betty Gow, who drank silver polish, which, as you know only too well, contains arsenic. And so, in Murder on the Orient Express, Charles Lindbergh Jr. becomes Daisy Armstrong. The nightmarish kidnapping sequence — in flashback — is genuinely creepy and unsettling, and if I viewed this alone late at night, I might even find it a little bit frightening (oh, big softie Lucozade!), with its spinning headlines (like sensational newspapers of the time), and the illustrated diagrams and the grotesque, but strangely compelling, pointing arrows — DAISY FOUND SLAIN — set to Richard Rodney Bennett's eerie, distorted incidental music. Incidentally, the wedding cake splendour of the Armstrong residence, supposedly set in Long Island, is actually High Canons House in Hertfordshire, built in the very early 19th century.

Less unsettling is the sheer star quality of the various suspects, which some critics found too much. A star too far? John Gielgud’s splendid butler, Beddoes; Lauren Bacall’s ghastly Mrs Hubbard, Anthony Perkins’ nervous, blazer-clad secretary (fountain pens clipped to top pocket); Rachel Roberts’ rather Lotte Lenya-ish lady’s maid to HSH the Princess Dragomiroff, played by Dame Wendy Hiller; Sean Connery’s Indian Army major (“twelve men, good and true”), Michael York and Jacqueline Bisset’s glamorous Hungarian aristos, and Richard Widmark’s unsavoury mafioso, the antiquities dealer, Samuel Ratchett — silk pajamas and an Amber Moon. Vanessa Redgrave, incidentally, steals the show in a marvellous performance as the vivacious, love-struck Miss Debenham. I’m also a fan of Albert Finney’s intense, fastidious, heavily-made up and greased Poirot, for which he received an Oscar nomination, altho’ he was also criticised at the time for ‘a lack of warmth’. Coldy analytical. But then we all have our own favourite Poirots, do we not? For many, it’s the avuncular charm of Peter Ustinov. For others, it has to be David Suchet, considered by the Christie aficionados to be the definitive version — or, at least, the performance closest in character to the books. Dame Agatha, herself, is said to have had mixed views on Finney’s performance.

Murder on the Orient Express (1974) won a host of nominations in the 1975 Academy and BAFTA Awards for best actor (s), best cinematography, best writing, best costume design and best music (original dramatic score), with Ingrid Bergman winning Best Actress in a Supporting Role for her portrayal of Greta Ohlson, the ‘backward’ missionary. Inexplicably, Richard Rodney Bennett failed to win the top prize. Wonders will never cease. Otherwise the film was a critical and commercial success, with Roger Ebert describing it as a ‘splendidly entertaining movie’, a ‘loving salute to an earlier period of filmmaking’ and praising Albert Finney’s performance as ‘brilliant and high comedy.’

So there you go. Murder on the Orient Express. The 1974 version! I watched the film via Amazon Prime Video digital download, and it’s also available to buy on DVD and Blu-ray, altho’ surprisingly, I couldn’t find a luxury edition with all the documentaries, enlightening commentary, trailers and other goodies, which we’ve come to expect. Still, I hope you enjoy this version as much as I did. Amber Moons for this one.

Enjoyed the ride? Then hop aboard every Friday with a paid subscription — just £5 a month or £50 a year. Film for grown-ups, with a splash of Cold Duck. First class all the way — with full access to our archive of 144 films (and counting). And if you liked this piece, please hit the ❤️, leave a comment, or share with a friend.

Great write-up Luke, as per normal. I'm rather haunted by 'a Teutonic sparkling wine made in the United States'.

Luke, your interest in the "art deco" revival in several of your pieces, prompts me to recall that the term "art deco" was only coined in the last years of the 60's ( I believe the term was first used in print in c 1968 I the Times?)

Once the period had a name and an identifiable set of defining elements, it suddenly became ripe for pillaging.

We must have been youngsters, but I recall a profusion of 20's styled shops, fast food outlets and films which mined a very recent past for visual themes.